Should investors be preparing for deflation?

14th April 2014 12:48

It is the old enemy. Inflation is something we all, as investors, have grappled with - at annual rates of up to 25% - in the UK during the past 50 years.

But could we soon face having to cope with a threat from the opposite end of the monetary scale: deflation, or persistently falling prices?

Could the pound in our pockets start growing in spending power, instead of shrinking?

It has not happened here since the early 1930s. Yet economists have begun to dust off their old history books and wonder.

After all - returning to more modern times - deflation has dogged Japan for more than 20 years.

The Japanese experience has seemed a rather faraway phenomenon, something to do perhaps with Japanese culture and the country's strange demographics and steadily declining population.

Global concern

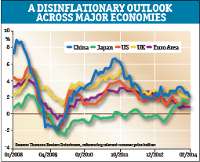

Even the Americans are getting worried: despite massive doses of quantitative easing, inflation is no more than 1.6%. Inflation has fallen to 2% in China.

And here in the UK, Consumer Prices Index inflation has drifted down from 5% to 1.9% over the past two and a half years. This downwards trend has persisted, despite the modest pickup in global economic growth.

History tells us there is a simple way to adjust our portfolios for deflation: we should sell equities and property, and switch into monetary assets, notably fixed-income bonds and bank deposits.

Between 1922 and 1932 retail prices fell consistently, at a rate averaging 4.1% a year. UK equity prices fluctuate, but barely showed a net change over that period.

Government gilt-edged bonds, however, showed strongly positive returns, with prices rising as yields declined from 4.5 to little more than 3%.

How differently it worked out in the immediate post-war period, when persistent inflation returned at an average rate of 4.1% in the decade of the 1950s.

During those 10 years, long-dated gilts lost nearly a third of their nominal value. But equities tripled in value - out of the revival of inflation came what was dubbed in the late 1950s 'the cult of the equity'.

Equities perform best at moderate inflation levels of, say, between 2% and 8%. The recent 2014 edition of the annual Barclays Equity Gilt Study, which plots more than a century of bond and equity returns, calculated a "sweet spot" of 3% inflation for the US stock market. But high inflation is damaging to equities, and so too is deflation.

Still, investors can cope with deflationary conditions by switching into bonds. Politicians, though, have no such escape route.

Deflation can have deadly implications for economies and governments. Deflation is, in effect, an increase in the value of money over time, benefiting patient savers but squeezing borrowers, not least governments, which can see their tax revenues fall in money terms and their debts mount.

Deflation would severely challenge the UK government's policy for the past five years, which has been to punish savers and reward borrowers.

The Bank of England interest rate has been slashed to 0.5% and cannot be cut much further. If a cut to -2%, for example, were attempted through a levy on bank deposits, there would be a public stampede into bank notes or offshore bank accounts.

Deflation tends to enhance economic depression by suppressing demand. The late 1920s and early 1930s were grim times for unemployment.

Governments will fight like tigers to avoid it and restore inflation - which around the world is being targeted at about 2%.

The practical challenge for investors, therefore, is not to get ready for persistent deflation, but to anticipate the measures governments might resort to to avoid a falling-price trap.

Here, we could take a leaf straight from Japan's textbook. For more than 30 years Japanese equities crashed, then languished.

But in late 2012, the Japanese government, led by Shinzo Abe, launched an aggressive campaign to jolt the country's economy out of decades of torpor using measures dubbed 'Abenomics'.

Public spending was boosted, monetary policy was eased and the Bank of Japan set a target of 2% inflation - which amounted to a big change, given that the average annual price level change for the previous 10 years had been about -0.5%.

As a result of Abenomics, the yen crashed and the Tokyo stock market rose strongly in value by more than 70% in a year. Not surprisingly, Japanese government bonds fell sharply in price.

The global economic jury is still out, though, on whether Abenomics will work. Inflation has turned positive, but only to the extent of about 1%, most of which reflects the rise in price of imports following the devaluation of the yen.

Eurozone struggle

Problems paralleling those of Japan in recent years now menace the eurozone. Negative shocks have been experienced across the zone as the European Central Bank has struggled to stabilise the euro and the European banking system.

Normally, a central bank can cut interest rates to stimulate a flagging economy. Cheaper money boosts demand in the economy and pushes activity back to a targeted equilibrium - of 2% inflation in the case of the eurozone.

But the interest rate for the euro is already down at 0.5% and the interest rate weapon is therefore short of ammunition.

This means the eurozone economy could flip into an alternative equilibrium where prices are locked into a falling trend. It may never happen, but investment market strategists are taking it seriously.

Here in the UK, deflation seems a long way off. Falls in energy and food prices have nudged inflation down, but this is probably temporary.

More sinister, perhaps, is the continuing weakness of average pay, a consequence of immigration and the influx of cheap imported goods, which has put pressure on UK employers.

There are global effects here, and if deflation becomes established in the eurozone and the US, it's unlikely the UK could escape.

It might be prudent for UK investors to raise their weightings in bonds and reduce those in equities, but gilts are unattractive - today they yield no more than they did in the deflationary early 1930s. My judgment is that investors should stay with equities through what could prove to be a troubled period ahead.

Nearly six years after the shocks of 2008 and 2009, the global economy remains on a knife-edge. The central banks may have to embark on a further round of 'extraordinary' measures. The risks for investors are rising again, although there are positive opportunities too.

Editor's Picks