Absolute return funds can miss the point

8th December 2015 17:32

The claim that targeted absolute return funds can deliver positive returns in any market conditions is often viewed with thinly veiled scepticism by private and professional investors alike. It is the sort of claim the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) frowns upon. Indeed, the claim is undermined by the funds' compulsory disclaimers on their promotional materials, which remind us that the value of our investments can go down as well as up.

Nonetheless, numerous investors have bought into this undeniably attractive prospect. The targeted absolute return sector - the fifth-largest of the Investment Association's (IA's) 36 sectors - boasts £52.8 billion of assets under management (as of 30 September) and consists of a wide range of funds invested in a number of regions and asset classes. The sector is consistently among the IA's top five monthly bestsellers, suggesting that investor appetite for absolute return strategies is strong.

Testing times

This year has arguably been an ideal time for testing the claims of absolute return funds. Market events, including the re-emergence of the Greek sovereign debt crisis in June and China's spectacular stockmarket crash in August - which sparked a global sell-off now known as Black Monday - caused widespread volatility and led to big losses across global stockmarkets.

During August, the worst month for markets this year, main developed market indices, from the to the S&P 500 and the Nikkei 225, shed around 5% of their values. Markets in China and emerging economies fared even worse. China's Shanghai Composite and Brazil's Bovespa indices shed 13% over the month.

(click to enlarge)

In the UK fund space only five IA sectors reported positive returns in August: UK gilts, UK index-linked gilts, global bonds, money market and short-term money market (bonds or cash).

On average, absolute return funds shed 0.4% during the month. This was, however, the smallest loss of any equity-inclusive sector over the period and less than the sterling strategic bond sector's 0.7% loss. It was also smaller than the IA mixed investment 0-35% shares sector's 1.7% loss, which is arguably one of the absolute return sector's closest competitors.

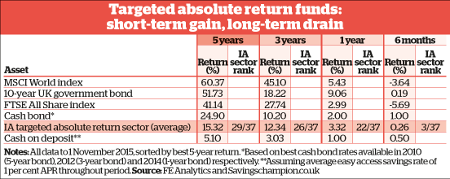

Thus, over one of the most volatile months for global equities seen since 2011, it seems targeted absolute return funds did protect investors in relative terms. Moreover, in the six months to 1 November, the targeted absolute return sector was the third best-performing IA sector out of 37, returning 0.26%, behind property and UK smaller companies - the latter enjoying an unusually positive year, despite global conditions.

Low volatility at a cost

Low volatility is, for some, the key attraction of absolute return funds, and the reason many investors look to them as a way to diversify their portfolios at the cost of potentially greater returns from riskier asset classes and sectors.

However, not everyone believes low volatility is worth the price investors have to pay for some funds. Barry Norris, manager of the Europe-oriented , says: "We are concerned that the emphasis on low volatility in isolation means far too many funds only deliver mediocre, 'cash plus' returns, without the actual safety of cash.

"But while cash does not charge an annual management fee, this is not the case with low volatility funds, and it is questionable whether it is appropriate for many of these funds to even apply the commonplace annual management charge (AMC)."

According to Norris, the positive return delivered by many low-volatility absolute return funds is virtually wiped out once fees are taken into account. Moreover, he says many funds remain highly correlated to stockmarkets, making them poor diversification tools.

Instead, he argues that, at their core, absolute return funds should aim to significantly outperform the average market return. Otherwise, there is little point in their existence.

Long and short strategies

One way he suggests absolute return funds can do this is by using "long" and "short" strategies of the type his fund employs, where a manager buys both conventional long equity holdings and derivatives that bet against, or short, share prices. This type of strategy, Norris argues, ensures portfolios will typically be less correlated with the wider market, so they will have a greater chance of outperforming conventional indices.

To date, this strategy has worked well for Norris, as FP Argonaut Absolute Return has delivered the second-best return in the 90-strong sector over three years to 1 November (70%) and the fifth-best return over one year (19%).

These returns also compare favourably with mainstream European equity returns: the STOXX Europe 600 index (which represents large, medium and small companies across 18 European countries) returned just 36.3% over three years and 5% over one year.

employs a similar long/short strategy in UK and global equities and has also performed well in recent years, delivering the strongest three-year return in the sector (95%) and the second-strongest one-year return (25.8%). The fund was also the best performer in the entire IA fund universe during stormy August, returning an astonishing 7% over the month as equities took a widespread hammering.

Other absolute return funds of note include , which returned 3.9% during August. The tiny £9.9 million fund is also the fourth-best performer over one year, with a return of 20%.

is the best performer in the sector over one year, returning 25.9%, while former Money Observer Rated Fund is the best long-term performer in the sector, returning 150% over five years. Perhaps unsurprisingly, all three funds use fairly aggressive long/short investment strategies.

Bond bind

The worst performers in the sector over one and three years are, predictably, funds invested in poorly performing assets such as bonds, particularly Asian and emerging market bonds. Other notable turkeys include , which has shed 9% over the past year despite fishing in the same pond as Argonaut, and absolute return fund-of-funds , which has gained just 1.6% over three years and lost 2% over one year.

Arguably more interesting, though, is an examination of the performance of some of the most popular low-volatility funds in the sector. These behemoths, which boast billions of pounds under management, are generally responsible for the strong inflows into the sector.

The largest by far is Money Observer Rated Fund , otherwise known as GARS, which recently amassed an astonishing £40 billion of assets under management across its various incarnations.

It's an undeniably popular fund, but has returned just 4.4% over one year to 1 November and around 15% over three years. Similarly, fellow Money Observer Rated Fund , the second-largest in the sector, with £9.3 billion of assets under management, has returned 2.8% over one year and 10.6% over three years, a mere fraction of that delivered by the sector's top performers.

, the third-largest absolute return fund in the sector, with £4 billion of assets under management, has meanwhile returned just 4.2% over one year and shed 0.6% over 6 months, while (£3 billion) has returned 4.1% over the year (although it has returned a much better 23.3% over three years).

All these funds market themselves as low volatility and/or low risk, and all are hoovering up institutional investment from large pension funds as well as wary private investors.

Long-term, low volatility comes out in the wash

While these funds undeniably have lower volatility than Argonaut and City Financial, for example, which can be fairly choppy, this is of questionable value.

Returning to Norris's point, GARS' one-year gain is reduced to just 2.8% once its 1.6% ongoing charges figure is deducted, while most investors will also be paying platform and/ or adviser fees on top. It is feasible that savers could have done just as well if not better in a cash deposit account or savings bond, the best of which are currently paying around 2%.

Moreover, for long-term investors, low volatility often comes out in the wash. While the absolute return sector rarely posts a loss, its gains reduce significantly over time, with the sector among the worst 10 performers in the IA universe over five years and the worst 11 over three years.

The sector has also underperformed mainstream indices, including the MSCI World and FTSE All-Share, by between 4.5 and 9% a year since 2012. Thus, as ever, investors are well advised to question what they are paying for and why when it comes to absolute return funds.

This article is for information and discussion purposes only and does not form a recommendation to invest or otherwise. The value of an investment may fall. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Editor's Picks