An impressive profit generator

24th June 2016 16:25

by Richard Beddard from interactive investor

Share on

As long as the industrialisation of the food supply continues, should prosper. Constraints imposed by its customers make it slow to adapt to change, though.

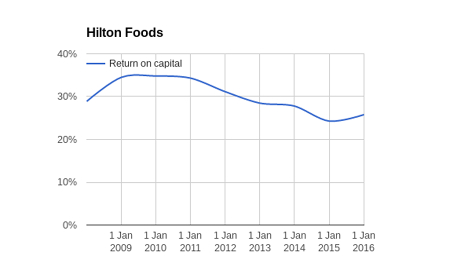

Apart from the fact that meat packing is about as glamorous as a rainy day in summer, this is what attracts me to Hilton Foods: over the last eight years profitability has been creeping downward from percentages in the low thirties to the mid-twenties, but it's still high enough to mark Hilton out as a very successful business and the modest decline may not be irreversible.

In recent years, Hilton has built new packing and processing facilities in Huntingdon, UK, and Vasteras, Sweden, swelling its capacity and the capital it employs. If it's not yet using all the capacity, profitability, the return on the capital, may improve as it sells more beef (and pork and lamb).

There is an alternative explanation for declining profitability though. Recent years have been tough ones for Hilton's customers, like . Hilton was established to supply Tesco in the UK in 1994, and since then it has slowly added customers in continental Europe and most recently Australia.

Mirroring the increased dominance of supermarkets, the meat packing industry has consolidated into a relatively small number of suppliers capable of sourcing and processing large volumes of meat safely and with full traceability.

The trend towards centralised meat packing continues, says Hilton, "albeit at different speeds around the world", suggesting perhaps that Hilton's biggest markets in Western Europe are mature, and better opportunities for growth exist elsewhere.

Europe is where almost all of Hilton's profit is made, though, and the competitive pressure on its customers to drive down prices is probably feeding through to the supplier.

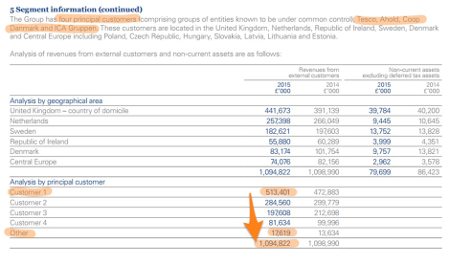

The big risk, the first risk listed in Hilton's strategic report, is customer concentration. Hilton only has a handful of, consequentially, very significant customers. Here's the footnote, showing just how much it depends on four customers, and two in particular:

Since almost half of Hilton's revenue comes from the UK and the Republic of Ireland, and more than a quarter from the Netherlands, Tesco must be Customer One, which earns Hilton 47% of its revenue. is number two, earning 25% of revenue. Together, Hilton is dependent for almost three quarters of its revenue on these two giant retailers. Revenues from retailers other than the "big four" account for less than 2% of revenue.

Hilton's strategy is to bind those customers closely. They sign five- or ten-year supply agreements specifying "revenue parameters" that enable Hilton to invest with some confidence. The contracts aren't enough to ensure Hilton's long-term profitability, though. They contain clauses to keep the prices it charges competitive, and supermarkets can negotiate better terms at the end when the contracts are renewed. Due to the length of the contracts, it would take up to a decade for a deterioration in the terms to show up fully in the company's results.

Over the long-term, Hilton must continue providing a better service, or sourcing, processing and packing meat at ever lower cost than rivals if it is to maintain high levels of profitability while its customers are negotiating lower prices. It probably needs to do both. There are hints in the annual report of how Hilton is defending profitability through automation and service.

The report brings to mind a futuristic scene: robots efficiently sorting packaged meat for despatch to individual stores at Hilton's eight meat packing facilities. New centres of excellence will work with equipment suppliers to develop bespoke technology and make Hilton even more efficient.

Seven facilities are dedicated to a single customer. Huntingdon supplies Tesco, for example, while another facility in Drogheda supplies Tesco Ireland and Zaandam supplies Albert Heijn, part of Ahold, in The Netherlands, Belgium and Germany.

The exception is Tychy in Poland, which to achieve the scale it needs to operate efficiently supplies Ahold and Tesco in Central Europe and Rimi in the Baltic states of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia. Rimi is owned by ICA of Sweden, which along with Coop Danmark completes Hilton's list of significant customers.

Each facility has an autonomous "self-sufficient" management team, which the company says enables closer customer relationships.

Hilton aims to provide a unique service to those customers, helping them identify consumer trends and develop products. It has established two innovation centres staffed by chefs and food technologists who work with customers and flavour supplies to take meaty concepts into mass production.

Technology, service, more products and more capacity may enable Hilton to grow profitably. In the nine years I have measured, revenue has more than doubled, profit almost doubled and, despite heavy investment, cash flow has been strong too.

Chief operating officer Philip Heffer who has been with the company since it was founded in 1994, and chief executive Robert Watson, who joined in 2002, have stakes in the company that dwarf their admittedly generous annual salaries and bonuses. As major shareholders they have a strong incentive to ensure the future prosperity of the business.

But the trend in profitability, albeit a decline from very impressive to merely impressive levels, shows that Hilton is constrained by what its big customers will pay for meat. Hilton thrived while the supermarkets grew, but long contracts and the heavy investment required to fulfil them means Hilton will be slow to adapt and profit from the growth markets of this decade, which are convenience stores and markets beyond Western Europe.

Reading between the lines of the annual report, I don't think Hilton's customers will allow it to grow in established markets by selling meat to their competitors. Winning new customers, probably means opening facilities in new territories. A joint venture with a new customer, Woolworth, to build new facilities in Bunbury, Australia (built in 2013), and Melbourne, Australia (built in 2015) may be the template.

A share price of 497p values the enterprise at £383 million, or about 16 times adjusted profit. The earnings yield is 6%.

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard

This article is for information and discussion purposes only and does not form a recommendation to invest or otherwise. The value of an investment may fall. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.

Disclosure

We use a combination of fundamental and technical analysis in forming our view as to the valuation and prospects of an investment. Where relevant we have set out those particular matters we think are important in the above article, but further detail can be found here.

Please note that our article on this investment should not be considered to be a regular publication.

Details of all recommendations issued by ii during the previous 12-month period can be found here.

ii adheres to a strict code of conduct. Contributors may hold shares or have other interests in companies included in these portfolios, which could create a conflict of interests. Contributors intending to write about any financial instruments in which they have an interest are required to disclose such interest to ii and in the article itself. ii will at all times consider whether such interest impairs the objectivity of the recommendation.

In addition, individuals involved in the production of investment articles are subject to a personal account dealing restriction, which prevents them from placing a transaction in the specified instrument(s) for a period before and for five working days after such publication. This is to avoid personal interests conflicting with the interests of the recipients of those investment articles.