When to keep expensive shares

30th September 2016 16:09

by Richard Beddard from interactive investor

Share on

There's a quote in annual report arranged between pictures of Sir David McMurtry, the company's chairman, chief executive and co-founder and John Deer, deputy chairman and the other co-founder. They're saying in unison:

"We have tried to build a different company. Different in how we apply technology to real world problems; in how we invest for the long-term; in how we manufacture rather than outsource; in how we work in partnership with our customers."

It would be easy to dismiss this as propaganda, but there's a lot riding on it. A share price of £26.30 values the enterprise at nearly £2 billion, or about 30 times adjusted earnings. The earnings yield is just 3%. That's a rough and ready way of saying if Renishaw doesn't grow, investors buying the shares at today's price can expect no more than a miserly 3% return.

If you were to judge Renishaw by its past performance, you might come to the following conclusions:

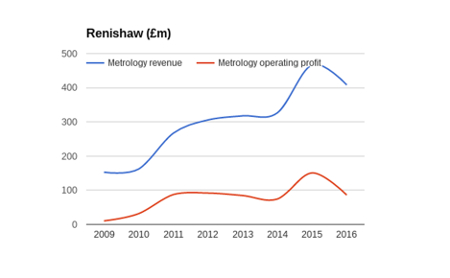

1. It's growing. Over the last ten years it's grown revenue at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 9.5% and profit at 8.5% CAGR.

2. It's growing profitably. Average return on capital is 17%, although it fluctuates quite markedly.

3. It has no debt.

4. Cash flow is relatively weak. In a typical year, it's only about 44% of profit. 2016 was below average. Capital expenditure used up almost all the cash Renishaw earned from operations. The remainder was only 13% of adjusted operating profit.

The most likely explanation for the discrepancy between accounting profit and cash is the spending Renishaw must do to grow.

Bumper investments

Renishaw invests in developing new products, building and equipping new factories and warehouses, and new offices to train, support and sell to customers around the world. Some of these costs will be expensed, immediately reducing profit, but much of it will only be charged in part to profit, and the remaining cost spread out over future years. It's depreciated, or amortised.

As a general rule, past profitability cannot be taken for grantedThis accounting treatment should give a fairer impression of the firm's performance as it matches costs to revenues, so profit in one year isn't penalised by the cost of investment that will benefit the company over many years.

Renishaw also maintains stock levels so it can deliver to customers on time. As it sells more stuff, therefore, it must fund more stock.

Since Renishaw has reinvested cash profitably in the past, it's tempting to believe the bumper investments it's made in recent years should mean more profit in the future. But, as a general rule, past profitability cannot be taken for granted. Sensing profit, competitors muscle in on highly profitable companies, which brings me back to McMurtry and Deer, and their quote.

What makes it different?

What makes Renishaw different? What can give us confidence the investments Renishaw is making now will lead to a more prosperous future?

The company makes machines that improve the performance of other machines. They calibrate, automate and test machine tools. It's also used its expertise in metrology, measurement, to invent more exotic machines: additive manufacturing machines (aka 3D printers) and surgical robots for example.

Sometimes Renishaw's metrology products are incorporated into machine tools by their manufacturers, although Renishaw prefers not to depend on these large customers, and increasingly sells directly to their end users, manufacturers of things: components for planes, cars, tractors, industrial and medical equipment and smartphones.

A case study in the annual report shows how High Tech, a manufacturer of titanium aircraft components, used Renishaw's Equator gauging system to test every part had been manufactured to the correct specification. Equator inspected 150 features, the number of bores, thicknesses and measurements to a tolerance of plus or minus 24 microns, saving High-Tech time and money.

Do it yourself

If Renishaw has a superpower, it's self-reliance. If it needs something done, as far as possible, the company says, it does it itself. Although it uses distributors in some places, it operates subsidiaries in 28 countries and representative offices in six others. To make machines, it uses its own machines. It does the machining, the anodising of aluminium components and the assembly and testing of electronic Printed Circuit Boards.

Its healthcare division uses additive manufacturing machines (3D printers) made by its Metrology division. Ongoing investment in Miskin in South Wales has increased its capacity for component part manufacturing as well as providing a healthcare training facility and product demonstration area.

Demand for RSW's machines depends on demand for the components they help to makeRenishaw's established "Solutions Centres" in Europe, North America and Asia to accelerate the transition of additive manufacturing from a niche prototyping technology to the mainstream. The centres will help customers design products for additive manufacturing and develop production processes.

Renishaw says it has more control over the quality of its products, but this isn't the modern textbook way to run a business. Vertical integration is a bit old hat. Businesses are supposed to do the things they do best, design, say, and outsource manufacturing and distribution to specialists that can do them better, or cheaper, or both.

Maybe Renishaw is the exception that proves the rule (or maybe the rule is wrong!)

Renishaw's kryptonite is the one thing it can't control, its customers. Demand for Renishaw's machines depends on demand for the components they help to make. A good product, customisation, advice, and training encourage loyalty but during periods of contraction, customers don't buy, so profitability and growth is lumpy.

In 2009, during the Credit Crunch, the company retrenched significantly. Rapid growth followed, although 2015 was an exceptional year due to one-off sales to consumer electronics companies in the Far East.

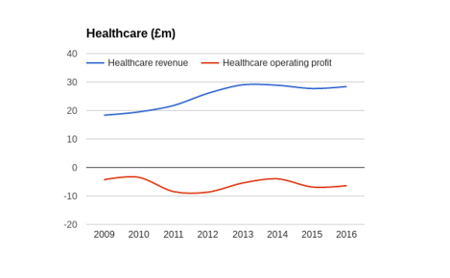

The other question on my mind is whether investment in whizz-bang technologies like additive manufacturing and surgical robots, will pay off. We don't know if Renishaw is losing money on additive manufacturing because its part of Renishaw's massive, profitable Metrology division, but its much smaller healthcare division, which manufactures dental bridges, surgical robots and spectroscopes, has been loss-making since before the company started reporting on it separately in 2010.

Establishing new technologies takes a long time, so Renishaw's ability to soak up losses may prove commendable in the long run.

It's likely that McMurtry and Deer have fashioned a unique business. They've run it since they spun it out of Rolls-Royce. But still I have misgivings, principally the high levels of investment and its unclear impact on profit. Profit in 2016 was double profit in 2006, but disregarding an exceptional year in 2015, it's been flat since 2011.

There's a halo effect that drives investors to buy growing companies, particularly if there is a good story attached: revolutionary technology, inspirational founders, different ways of doing things. We must try and puncture these stories because, if they're not true, the share price almost certainly overvalues the company.

I'm still buying it, though. The story that is. But with the share price at nosebleed levels, Renishaw is a tough hold.

I'm on a panel of investors at the next ShareSoc (UK Individual Shareholders Society) Masterclass on 14 October that also includes SharePad analyst Phil Oakley and ISA Millionaire Leon Borras. Phil's going to give a presentation on cash flow statements. Then we're going to talk about our latest, and our worst investments. Lots to talk about then. For a £10 discount on the ticket price use the code 'beddard' when you register. You'll also get a complimentary six months membership of ShareSoc.

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard

This article is for information and discussion purposes only and does not form a recommendation to invest or otherwise. The value of an investment may fall. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment advise

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.

Disclosure

We use a combination of fundamental and technical analysis in forming our view as to the valuation and prospects of an investment. Where relevant we have set out those particular matters we think are important in the above article, but further detail can be found here.

Please note that our article on this investment should not be considered to be a regular publication.

Details of all recommendations issued by ii during the previous 12-month period can be found here.

ii adheres to a strict code of conduct. Contributors may hold shares or have other interests in companies included in these portfolios, which could create a conflict of interests. Contributors intending to write about any financial instruments in which they have an interest are required to disclose such interest to ii and in the article itself. ii will at all times consider whether such interest impairs the objectivity of the recommendation.

In addition, individuals involved in the production of investment articles are subject to a personal account dealing restriction, which prevents them from placing a transaction in the specified instrument(s) for a period before and for five working days after such publication. This is to avoid personal interests conflicting with the interests of the recipients of those investment articles.