New chapter beginning for income seekers

27th October 2016 09:40

by Tony Yarrow from ii contributor

Share on

Interactive Investor is 21 years old. To celebrate, our top journalists and the great and the good of the City have written a series of articles discussing what the future might hold for investors.

I'm writing as a "freelance income investor": a fund manager who can source income from anywhere it arises, without restriction. Twenty-one years ago, in 1995, our main sources of income were fixed interest, shares and commercial property. Fixed interest meant government stocks (gilts) and corporate bonds.

The shares we freelancers bought were mainly in UK companies, as these paid better dividends than those available almost anywhere else. Moreover, dividend choice in the overseas markets was so limited that the Investment Association's global equity Income fund sector, which is so popular today, did not exist.

There was less investable commercial property then too, and fewer funds to choose from. No one knew what a real estate investment trust (REIT) was, and there were no bricks-and-mortar investment trusts. And in those far-off days, deposit accounts paid a real income.

Since 1995, not only has the choice widened in existing asset classes, but we have seen new income-paying asset classes emerge, including private equity, infrastructure, alternative energy, peer-to-peer lending and aircraft leasing. The period since 1995 falls naturally into three unequal sections:

1995-2000

In the two decades ending in March 2000, UK shares rose roughly sevenfold in value. They were everyone's favourite asset class. Scottish Equitable launched its High-Equity With-Profits Bond, and everyone knew what that meant - a with-profits fund with superior returns, one that beat its competition by having fewer of those boring gilts. The 1980s were a particularly difficult time for gilts.

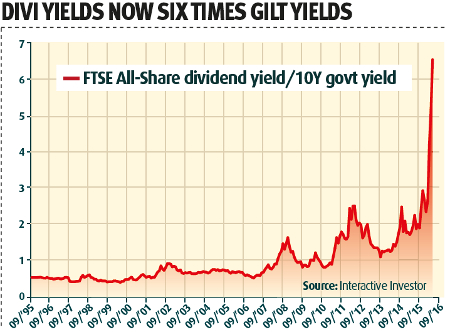

Boots' pension scheme's switch from shares to gilts in 1999 was a brilliant example of market timingThe relatively high level of inflation made their fixed coupons look unattractive, and equities outperformed them every year. The 1990s were little better: by the late 90s the income yield on a typical basket of UK shares was around 3%, roughly half of what could be expected from gilts or cash, but no one minded - for total return, shares were the stand-out asset class over all periods.

In the autumn of 1999, the managers of the Boots pension scheme switched the entire portfolio from shares into gilts. Their explanation was that the fixed payments from gilts matched the pension's liabilities better than any other asset class. This was true, and also one of the most brilliant examples of market timing I have ever seen.

2000-2008

In 2000 the ending of the technology, media and telecoms (TMT) bubble profoundly changed the dynamics of the UK stock market. In the late 90s investors had been selling "old economy" shares to buy into companies that looked set to benefit from the commercial potential of the internet.

In 2000 income-paying shares were very cheap; they spent the next eight years being re-ratedThe former included the shares of housebuilders and construction firms, brewers, banks, tobacco producers, insurance companies and public transport operators.

These companies paid most of the market's dividends, so life was very difficult for equity income fund managers.

We had to choose between investing for yield and losing money, or investing in overvalued TMT companies with no yield. The year 2000 ushered in a golden period for income managers.

In that year income-paying shares were very cheap, and they spent the next eight years being re-rated. Good equity income funds beat the stock market every year from 2000 to 2006.

During this period, gilt prices began to recover and yields started to drop. The period 2000-07 was also a vintage period for commercial property investment. Usually, commercial property prices fall in a recession, and they had fallen sharply in the painful 1990-93 recession. There was a recession from 2000 to 2002, but commercial property prices continued to rise.

By 2007 commercial property had been rising for 15 years in a row and was dangerously overvalued. Yields were at extremely low levels - just as investors, with ever-increasing levels of debt, were joining the party.

During the harrowing financial crisis, the only safe income-producing assets were gilts and cashIn the financial crisis, nearly all investors were punished, particularly those owning indebted assets. Some of the newly launched property investment trusts were forced to close, with huge losses.

During this harrowing period, the only safe income-producing assets were gilts and cash. The shares of defensive companies with safe dividends fell, but by much less than the market. The new infrastructure funds proved to be a relative safe haven too.

2009-2016

Early in 2009 central banks, first in the US and then the UK, introduced quantitative easing (QE): they "created" money to purchase large amounts of government stock. In the UK the Bank of England has so far bought £375 billion of gilts, equal to £6,250 for each inhabitant of the UK.

QE reduces the availability of gilts, causing gilt prices to rise and their income yields to drop. Government borrowing becomes cheaper as a result of the policy. QE is also meant to create a "wealth effect" by inflating the values of other assets and encouraging the owners of those assets to spend money and invest.

The highest-quality corporate bonds, known as 'investment grade', are proxies for giltsHowever, criticism of the policy is growing. QE distorts asset markets and creates deficits in the pension funds of large companies. Result: the companies have to divert money into their pension schemes rather than make productive investments - the very opposite of what QE is intended to achieve.

The wealth effect helps a small minority of people, increasing inequality. In 2009 gilts prices quickly rose to a point at which we considered them un-investable, but they have continued to rise to the point where investors in government stock in many countries around the world, if they buy at today's prices, are guaranteed to make a loss. The highest-quality corporate bonds, known as "investment grade", are proxies for gilts.

These securities were hit hard during the crisis, but recovered strongly following the introduction of QE, and they have been expensive for the past six or seven years. The shares of the safest dividend-paying companies - bond proxies - held up much better than the overall market during the crisis, and have remained strong.

Some commentators believe these shares are now overvalued, but many investors would prefer the safety of bond proxies to anything riskier. QE may be responsible for the nervous attitudes of many investors.

For 21 years, markets have always delivered chances for income investors ready to take what comesThere is a sense that since the crisis "the can has been kicked down the road", fundamental problems in the system haven't been properly addressed and a day of reckoning is coming, perhaps when QE eventually unravels, or earlier if the authorities lose control of the situation. For the past seven years, we freelance income investors have been living on scraps.

Locked out of the vast gilt and corporate bond markets by their gravity-defying valuations, we have found value and yield in unfashionable cyclical shares and smaller companies, overseas equities, commercial property (which began to recover in 2013), private equity and certain less fashionable corporate bonds.

There is a feeling that we are now at the beginning of a new chapter. During the past 21 years, markets have never failed to throw up good opportunities for income investors prepared to take what comes. We hope that in this respect at least, the future will resemble the recent past.

This article was first published in our special publication 21: Twenty-one years of Interactive Investor. Download your digital copy for free here.

This article is for information and discussion purposes only and does not form a recommendation to invest or otherwise. The value of an investment may fall. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.