The curse of the growth investor

2nd December 2016 15:21

by Richard Beddard from interactive investor

Share on

is perhaps unusual among smaller companies in publishing precise financial targets up to three years into the future. There's a danger that investors take them as a given, or extrapolate from them, even though they have yet to be achieved.

The company has increased revenue at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 17% since it floated in 2005, and over the next three years it's set itself a target to increase revenue by between 10% and 15%, while keeping pre-tax profit margins above 17.5% (they were 19% this year, after certain adjustments).

While revenue growth has been fairly consistent, profit margins haven't always been that high. Around the turn of the decade, the company suffered a mortal blow to its original product line - disinfectants for machines that wash medical instruments like endoscopes - after the machine manufacturers acquired and specified their own disinfectants.

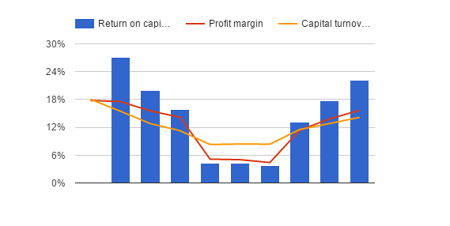

Tristel had developed alternative products, wipes and foams for cleaning simple medical instruments, and hospital surfaces, but the cost of rolling them out around the world, while simultaneously developing ranges for veterinary practices under the Anistel brand name and for laboratories and cleanrooms under the Crystel brand name, reduced return on capital from over 20% to under 5%.

Now profitability is back where it was, Tristel is growing profitably again.

There's an obvious need for disinfectant in hospitals, Tristel's biggest market by far, and particularly for Tristel's, because the chlorine dioxide formulation is efficacious and does not require expensive machinery.

In a decade, it has come to dominate the UK market. In cardiology departments, Tristel's market share is 95%, in ENT departments it's 78%, and in ultrasound departments it's 50%.

With the founders still managing the firm, it could be a very good long-term investment.

The cursed valuation

Except, that is, for the cursed valuation. A share price of just over 170p values the enterprise at around £70 million, more than 25 times adjusted profit. The earnings yield is just 4%. If the company doesn't grow profit, the returns don't look particularly appealing.

That Tristel will grow seems certain, though. Hospitals would like to limit their investment in machines to where there is no alternative, and rival manual disinfectants tend to be less efficacious or potentially more harmful to the user.

The company says it's moving into "uncontested space" abroad, just like it did in the UK, and with foreign revenue approaching 36% of the total, it's building up another barrier to entry.

Expect annual returns on an investment in Tristel at the current price of more than 4%Any company wishing to emulate Tristel must not only develop something as good without infringing Tristel's patents, which protect the delivery of its chlorine dioxide formulation in various forms, it must also stump up the money to get the products approved in each territory in which it wishes to compete.

In 2014, Tristel started the registration process in the USA, one of the more difficult regulators to satisfy. It hopes to have registered its first products early in 2018.

So we can expect annual returns on an investment in Tristel at the current price of more than 4%, but beyond the vague notion that Tristel's disinfectant will meet no more resistance as it spreads around the globe than a spilled pint of beer on a bar, I can't say how much they will grow.

Game of make-believe

So let's play a game of make believe.

Let's be prudent about the growth rate signalled by Tristel, and plug the bottom end, 10% annual growth in revenue, into a very simple model. Let's assume profit margins don't increase - even though they might, because Tristel has plenty of spare manufacturing capacity, so it can increase production without adding greatly to cost.

But let's say Tristel continues growing revenue and therefore profit for 10 years. The world is a big place and there is no reason to suppose it will stop growing after its three-year forecast.

Let's assume it stops growing after ten years, and continues in business earning the same profit forever.

How much would the shares be worth?

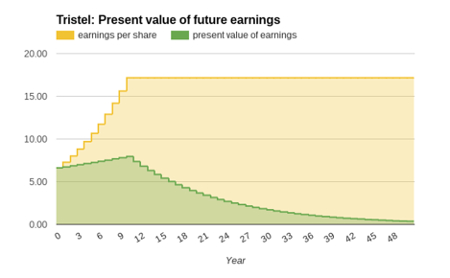

Well, they might be worth 168p. Straight up. After factoring in all that growth, they might be worth almost exactly what the shares actually cost today.

This model exposes the speculation in share prices of companies that are expected to growI didn't fiddle with the numbers to get the result I wanted. I made the assumptions, calculated how much the company would earn each year for fifty years if they were true, calculated what that money might be worth in today's money (its present value*) and added up all those earnings, which, in theory belong to shareholders.

The assumptions are heroic, the result a coincidence, and the scenario just one of many potential outcomes, but it gives an impression of what shareholders in Tristel expect.

That makes me cautious, because it exposes the speculation in share prices of companies that are expected to grow. Tristel may not be experiencing competition now, but we cannot be sure it won't in the future.

While overseas growth is a source of confidence, each country, and their regulatory and health systems, is different. The range of potential outcomes is wide.

Tristel could do much better than I've assumed if its products take off in the USA, for example. It could also do much worse.

This is the curse of the growth investor. It can do your head in!

*Using a discount rate of 8%, perhaps the most heroic assumption of them all. Like the growth rate, it's a made up number, the minimum annual return I expect from stockmarket investment over the long-term.

If I invest in Tristel, I have forsaken the opportunity to invest in another company or fund at an 8% return, a cost to be discounted from the growth in earnings (or return) from the share.

You can see in the table below the value of each year's earnings ('yellow'), and their discounted value ('green').

For the first ten years the discounted value of earnings increases because returns from the company are growing faster than my required return.

Thereafter they decrease, because earnings are no longer growing. The value of the firm is the sum of the 50 years of discounted earnings.

We can forget about the earnings after 50 years. In today's money, they're vanishingly small.

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard

This article is for information and discussion purposes only and does not form a recommendation to invest or otherwise. The value of an investment may fall. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.

Disclosure

We use a combination of fundamental and technical analysis in forming our view as to the valuation and prospects of an investment. Where relevant we have set out those particular matters we think are important in the above article, but further detail can be found here.

Please note that our article on this investment should not be considered to be a regular publication.

Details of all recommendations issued by ii during the previous 12-month period can be found here.

ii adheres to a strict code of conduct. Contributors may hold shares or have other interests in companies included in these portfolios, which could create a conflict of interests. Contributors intending to write about any financial instruments in which they have an interest are required to disclose such interest to ii and in the article itself. ii will at all times consider whether such interest impairs the objectivity of the recommendation.

In addition, individuals involved in the production of investment articles are subject to a personal account dealing restriction, which prevents them from placing a transaction in the specified instrument(s) for a period before and for five working days after such publication. This is to avoid personal interests conflicting with the interests of the recipients of those investment articles.