Cohort is a 'good investment'

22nd September 2017 16:19

by Richard Beddard from interactive investor

Share on

The closure of SCS last November, the business upon which was built, must have been a symbolic moment for the defence technology group. To understand where it's going, we must first look back, at where it came from.

Outlasting the enemy within

They say no battle plan survives contact with the enemy, and for a while after Cohort floated in 2006 it must have felt like that.

The launch vehicle was SCS, a training company founded by Stanley Carter, who had previously led a distinguished career in the army. His co-founder Nick Prest was ex-Ministry of Defence and the former boss of Alvis, a major military supplier.

Cohort would use its expertise and contacts to acquire small contractors and make them bigger, but after the first two acquisitions things started to go wrong.

Each business, the company intended, would act autonomously, responding rapidly to customers without the need to continuously seek head office approval.

This would distinguish Cohort from larger, more cumbersome rivals, but poor financial controls meant costs overran at SCS and SEA, which Cohort acquired in 2007.

As Cohort's attention turned inwards, the acquisition strategy was put on hold until 2014, by which time SEA had divested its loss-making Space division, the board had improved its oversight of large contracts, and Andrew Thomis, managing director of Cohort's first and most successful acquisition, MASS, had been promoted to group chief executive.

MASS provides software, services and consultancy to protect, analyse and interpret data, providing, managing, and supporting secure networks and electronic warfare databases. SEA has expertise is in communications and surveillance systems.

Cohort was experiencing growing pains at a particularly inauspicious time.

The government cut defence spending after the financial crisis, and the MOD brought more training and research in-house.

After a catastrophic decline in demand for training and consultancy, Cohort shut SCS down in November last year, and redistributed the remaining contracts to MASS and SEA. SCS was a victim of austerity.

Growing through austerity

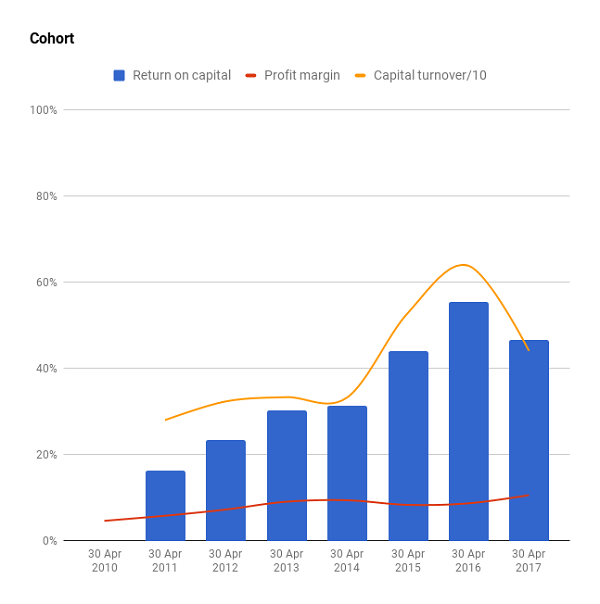

Perhaps the surprising thing about Cohort is profit has tripled in the last seven years. Until the financial year just concluded, it was ratcheting up return on capital as it put its houses in order:

The profit figure used in the return on capital calculation excludes the cost of amortising acquired intangible assets, which reflect the cost of purchasing businesses, rather than the ongoing profitability of the businesses themselves.

It also excludes the cost of redundancies at SCS and a provision for the lease on the subsidiary's head office, which it no longer needs.

Cohort's cash flow can be alarmingly volatile due to the timing of contract payments, but take the long-term average and you'll find it's highly profitable in cash terms too.

The initial promise, that a group of semi-autonomous specialist businesses can serve customers better than a monolith, may be one reason Cohort has been successful.

Because its subsidiaries are part of larger plc, customers may also be more confident awarding it large and long-term contracts.

Cohort's technology focus keeps it relevant as the nature of warfare changes and the importance of counter-terrorism grows.

Since Cohort has proven it can grow through adversity, it may make a good investment at the current share price of 400p.

It values the enterprise at about £190 million, 16 times adjusted profit.

While Carter is a non-executive director now, he retains a substantial shareholding, and so does Prest, who's chairman.

Chief executive Andrew Thomis and finance director Simon Walther, have been loyal executives, almost since the beginning. They'll probably keep up the good work.

The future, now…

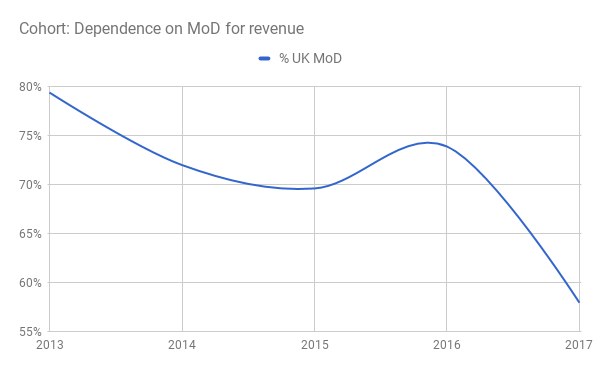

That's not to say everything's sorted. The prolonged degradation and sudden death of SCS stems directly from Cohort's dependence on the MOD, which in the year to April 2017 earned the company 31% of total revenue. Indirectly, as a subcontractor to companies supplying the MOD, Cohort earned a further 27% of revenue.

Although the government says spending on military equipment should rise again from 2018, Cohort is understandably cautious about the extent to which its biggest customer will open its wallet.

It's responding to austerity with a two pronged overseas assault, having acquired a foreign subsidiary, and become more product focused.

Looking abroad

The good news is that, while Cohort is still dependent on the MOD for most of its revenue, the proportion is coming down, mostly due to the acquisition of a majority shareholding in EID in June last year, two months into the financial year.

EID is a Portuguese supplier of communications systems to various European navies including the Royal Navy.

As well as adding a profitable business to the group, EID allows Cohort to trade with governments who, for political reasons, prefer not to buy British.

Product focus

To support its overseas push Cohort needs to supply things armed forces overseas will buy. Training and consultancy services are harder to scale and export than equipment and software.

While MASS and SEA provide scientists and specialists for research and training programmes, they design, manufacture and supply products too. EID, and MCL, which Cohort acquired in stages in 2014 and 2017, are equipment companies.

MCL integrates off-the-shelf components into communications and surveillance equipment, which means cheaper and faster product development for some applications.

2017: Not a banner year

The closure of SCS and the acquisition of EID are milestones, deeply etched in this year's results.

Revenue barely budged upwards in 2017, and would have fallen 14% were it not for EID.

Although MASS, remains the biggest contributor to profit, it didn't earn the highest profit margin as it usually does. That honour goes to EID too. Without EID, group profit would have declined 13%.

With EID, adjusted profit increased 22%. EID may not perform quite as well in future, it did more high-margin support work than usual in 2017, but since Cohort quotes a normal net profit margin of 20% for EID, it looks like it's going to continue vying with MASS to be Cohort's most profitable business.

While SCS was the principal casualty of MOD cutbacks, it was not the only one. Cohort helpfully provides a table breaking revenue down by capability.

The only three capabilities that grew revenue in 2017 were the highest earning, all of them product related.

The other categories, operational support, specialist expertise, training, studies and analysis and applied research, declined. All of them concern the supply of expertise.

Apart from SCS, SEA's research division felt the hardest pinch.

Evolution, not revolution

The MOD isn't going out of business. One day, perhaps not too far away, demand may rise again for training and consultancy, and Cohort will have retained the capability at MASS and SEA.

The MOD will probably always be Cohort's biggest customer, but it's sensibly seeking out others too, not just in defence, but civilian security markets like traffic enforcement and police forensic systems.

Short-termists will be anticipating higher profit in 2018 from increased orders, some delayed from the previous financial year, and full-year contributions from EID and the remaining 50% of MCL acquired in January 2017.

More importantly, though, Cohort's applying its expertise in technology to its own products, which it has always done, more than to people and projects, which it has also always done.

It's a shift of emphasis, not a wholesale change of business model.

Cohort is complicated for a small business and sometimes difficult to fathom. It has a maddening habit of naming its subsidiaries with three-letter acronyms that turn my notes into a mush of almost indistinguishable letters.

Despite its faults, and its two-steps forward one-step backwards journey, I think it's a good investment.

Contact Richard Beddard by email: richard@beddard.net or on Twitter: @RichardBeddard

These articles are provided for information purposes only. Occasionally, an opinion about whether to buy or sell a specific investment may be provided by third parties. The content is not intended to be a personal recommendation to buy or sell any financial instrument or product, or to adopt any investment strategy as it is not provided based on an assessment of your investing knowledge and experience, your financial situation or your investment objectives. The value of your investments, and the income derived from them, may go down as well as up. You may not get back all the money that you invest. The investments referred to in this article may not be suitable for all investors, and if in doubt, an investor should seek advice from a qualified investment adviser.

Full performance can be found on the company or index summary page on the interactive investor website. Simply click on the company's or index name highlighted in the article.

Disclosure

We use a combination of fundamental and technical analysis in forming our view as to the valuation and prospects of an investment. Where relevant we have set out those particular matters we think are important in the above article, but further detail can be found here.

Please note that our article on this investment should not be considered to be a regular publication.

Details of all recommendations issued by ii during the previous 12-month period can be found here.

ii adheres to a strict code of conduct. Contributors may hold shares or have other interests in companies included in these portfolios, which could create a conflict of interests. Contributors intending to write about any financial instruments in which they have an interest are required to disclose such interest to ii and in the article itself. ii will at all times consider whether such interest impairs the objectivity of the recommendation.

In addition, individuals involved in the production of investment articles are subject to a personal account dealing restriction, which prevents them from placing a transaction in the specified instrument(s) for a period before and for five working days after such publication. This is to avoid personal interests conflicting with the interests of the recipients of those investment articles.